Understand

We appreciate what we understand. The more we learn about the sperm whales, the greater our understanding of them as a species and culture. The best way to deepen our knowledge is through experience.

In this section we describe the methods and practices that have evolved to inform our research as citizen scientists. We present our most recent field reports, discuss the creation of our identification catalog and PIWWE protocols, provide facts about sperm whales, and open the conversation to enrich our collective knowledge of sperm whales.

We present our most recent field reports, discuss the creation of our identification catalog and PIWWE protocols, provide facts about sperm whales, and open theconversation to enrich our collective knowledge of sperm whales.

Research

During our field sessions we spend 20- 30 days aboard a support vessel where we search, observe, and enter the water to document the whales. Our study is conducted along the coastline of Dominica, a volcanic island that is part of the Windward Islands of the Lesser Antilles. The ocean floor drops abruptly to several thousand feet very close to shore along the west coast of the island, creating a calm, protected area for groups of resident sperm whales to feed, mate and socialize. It is also an ideal setting for observing the whales.

Our data collection has evolved over the years into a systematic process. We record the date, sea conditions, time, location (latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates), identity, gender, social association, and behavior of the whales we observe. We film all in-water sightings and record the time and duration of the encounters. Positive identification of the whales is often confirmed as result of our in-water observation, and at times only after reviewing the film footage.

At the completion of each field study I generate a detailed project report for the Dominica Department of Fisheries as a condition for obtaining the required permit for in-water activity with the whales. The report combines quantitative data with qualitative representation of the whales via still photographs, video footage, and in depth discussion of our observations.

The collective data, imagery and narrative depict a multilayered representation of the sublime intelligence, social proficiency, and singular personalities of the resident sperm whales. Through our multi-year study we are able to monitor the expansion and contraction of family units, track the physical growth of individuals, observe the evolution of their emotional maturity as the whales assume different roles within the family units, and witness the development of their distinct personalities as they age.

Our most recent reports can be found here:

Methods

Underwater Identification Catalog

The annual reports along with our growing image and video library enables us to correlate information about the whales from year to year. This has led to the creation of our own system for recognizing individuals which we use in conjunction with fluke identification information published by the Dominica Sperm Whale Project.

Whale identification is traditionally achieved by collecting images of their flukes as they lift their tail fins to dive below the surface. Sperm whales are differentiated by irregularities on the edges of the flukes created by scratches, gouges, and bites inflicted by predators. While the wounds eventually heal, the flukes never resume their original shape, thus enabling positive identification. The fluke contours change over time, making accurate data collection a challenging endeavor.

Lady Oracle - 2020

Lady Oracle - 2021

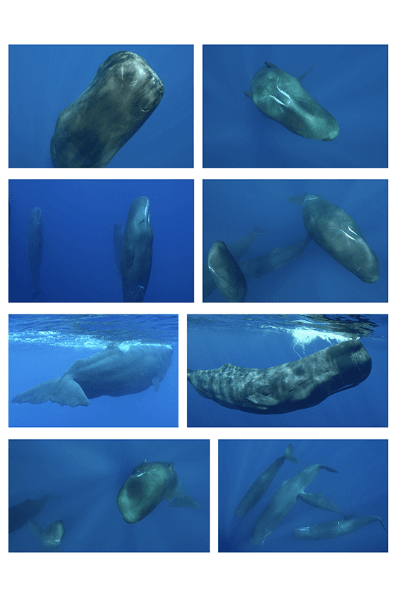

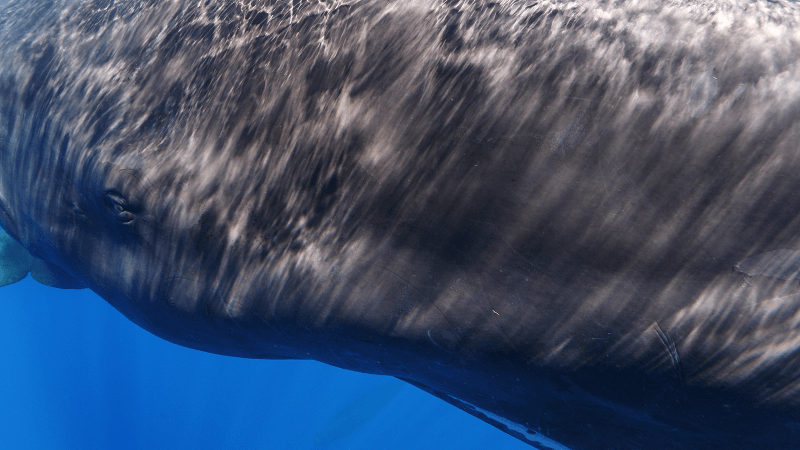

Our identification catalog highlights specific features of the whales that can only be seen underwater. These distinguishing markings maximize our ability to recognize the whales from our in-water perspective. The markings include permanent scars on the face and body, birthmarks, changes to the pectoral fins, and pigmentation on their lips. Like the flukes, some of these markers change due to their life experiences.

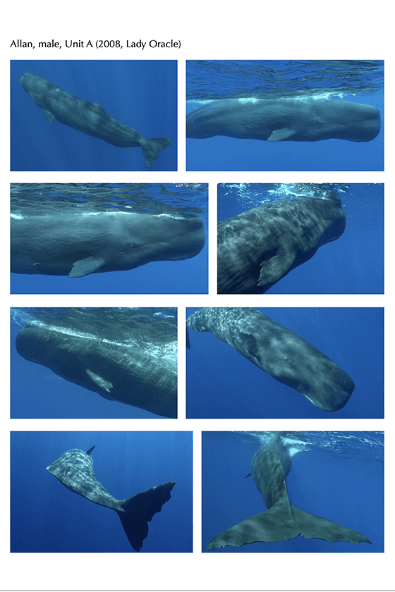

The catalog consists of two parts. In the field we use a series of quick-reference visual aids devoted to each social unit and individual whale. There is a page for every whale containing images of the individual in defined orientations.

These and other images are used as a reference to create the illustrations that are seen in part two of the catalog, presented in the Identify Section. Our extensive system helps us recognize the whales in the water, clarify individuals and social associations in our documentation imagery, and enable us to note changes in their physical features over time.

In-Water Observation Protocols

Central to our study has been the consideration of the impact of human involvement in the lives of wild cetaceans in their natural environment. An ongoing project objective has been to implement and refine protocols for in-water observation that prioritize the well-being of the whales.

We utilize a set of guidelines termed Passive In-Water Whale Encounter (or PIWWE) protocols formulated by Tom Conlin who has facilitated in-water encounters with humpbacks, blue, fin, and sperm whales for the past 30 years. A ‘PIWWE’ is defined as a passive, respectful, non-aggressive technique for interacting with whales. The intent is to allow for whales to willingly engage with humans by conscious choice.

The PIWWE protocol is a team effort involving the operator of the boat, the guide, and the in-water participants. The guidelines contain both logistical components and a specific mindset. The logistical aspects determine the way the boat is maneuvered to approach the whales in a non-threatening manner, how and where the researchers are placed in the water, and the manner in which they conduct themselves once in the water.

When circumstances allow, researchers enter water with an attitude of respectful reverence. The whales are approached quietly, calmly, and patiently, allowing them to acknowledge the presence of humans, determine their interest in us, and if they choose, initiate the encounter. It is the responsibility of researchers to earn the trust of the whales by behaving responsibly in their environment. The decision to engage and the nature of the encounter is determined by the whales.

This subtle orientation to approach and observe the whales on their terms has repeatedly proven to have a profound effect on the quality and duration of our in-water encounters. When regarded with respect, patience, and consideration for the integrity of their experience, sperm whales are noticeably more relaxed and willing to interact and be observed by researchers.

We will continue to monitor and describe the long-term relationship between humans and sperm whales, focusing on changes in their behavior based on how people interact with them during both surface and in-water observations. Our intention is to assist in making these practices safer, more conducive to productive research, and ultimately less disruptive to the whales.